Understanding the Profound Shift in Parent-Child Dynamics

The journey of becoming a caregiver for one’s parent marks one of the most significant transitions in adult life. We find ourselves standing at the intersection of filial responsibility and profound emotional complexity, where the roles we’ve known since birth undergo a fundamental transformation. This role reversal—where the child becomes the caregiver and the parent becomes the care recipient—challenges our identity, tests our emotional resilience, and redefines the very foundation of our most formative relationship.

When we assume the caregiving role for an aging or ailing parent, we’re not simply adding tasks to our daily routine. We’re navigating a complete restructuring of family dynamics that has been decades in the making. The parent who once provided protection, guidance, and unconditional support now depends on us for assistance with daily activities, medical decisions, and emotional stability. This shift creates a unique psychological landscape that requires acknowledgment, understanding, and intentional navigation.

The Emotional Complexity of Role Reversal

Grief and Loss Within the Caregiving Experience

We must acknowledge that caregiving often begins with grief—not necessarily the grief of death, but the grief of transformation. We mourn the parent we once knew: the strong, independent figure who seemed invincible. This anticipatory grief coexists with the present moment, creating a complicated emotional terrain where we’re simultaneously caring for our parent while processing the loss of who they once were.

The psychological impact of this role reversal extends beyond simple sadness. We experience a fundamental shift in our worldview. Our parents represented permanence, security, and the buffer between ourselves and mortality. When we become their caregivers, that buffer dissolves, forcing us to confront our own vulnerability and the finite nature of life itself.

Identity Reconstruction and Self-Perception

Throughout our lives, we’ve constructed our identity partly in relation to our parents. We’re someone’s child—a role that carries specific expectations, behaviors, and emotional patterns. When caregiving responsibilities emerge, we’re challenged to reconstruct our self-perception while maintaining the core of who we are.

This identity transformation doesn’t occur overnight. We gradually move from being the recipient of care to the provider, from being guided to being the guide, from seeking approval to making decisions on behalf of another. Each step in this progression requires us to release old patterns and embrace new responsibilities, all while preserving the fundamental love and respect that defines our relationship.

Practical Strategies for Navigating the Transition

Establishing Clear Communication Frameworks

Open and honest communication forms the cornerstone of successful role reversal navigation. We must create spaces for difficult conversations—discussions about health decline, financial matters, end-of-life wishes, and changing needs. These conversations, while uncomfortable, prevent misunderstandings and establish clarity during moments of crisis.

We recommend implementing regular family meetings where all parties can express concerns, share observations, and collaboratively make decisions. This structured approach to communication ensures that our parent maintains agency and dignity while allowing us to address practical caregiving concerns. Documentation of these conversations becomes invaluable, particularly when multiple family members share caregiving responsibilities or when legal and medical decisions require clear records of our parent’s wishes.

Setting Boundaries While Maintaining Compassion

The challenge of boundary-setting in caregiving relationships cannot be overstated. We must learn to distinguish between what we can reasonably provide and what exceeds our capacity—whether that capacity is physical, emotional, financial, or temporal. Sustainable caregiving requires us to establish limits that protect our own wellbeing without diminishing the quality of care we provide.

Boundaries might include designated caregiving hours, specific tasks we’re willing to perform, or emotional limits around certain topics or behaviors. We establish these not out of selfishness but out of recognition that we cannot pour from an empty vessel. Communicating these boundaries clearly and compassionately to our parent helps them understand our limitations while reassuring them of our ongoing commitment to their welfare.

Preserving Dignity and Autonomy in the Caregiving Relationship

Honoring Our Parent’s Independence

Despite physical or cognitive decline, we must actively work to preserve our parent’s sense of autonomy and self-determination. This means involving them in decisions about their care, respecting their preferences whenever possible, and finding creative solutions that allow them to maintain control over aspects of their daily life.

We might encourage our parent to continue activities they can safely perform independently, even if we could complete these tasks more efficiently. We can offer choices rather than directives: “Would you prefer to bathe in the morning or evening?” rather than simply announcing bath time. These small gestures of respect accumulate, reinforcing our parent’s dignity and sense of self during a period when much feels beyond their control.

Recognizing the Residual Parental Role

Even as we assume caregiving responsibilities, we acknowledge that our parent remains our parent. They possess decades of life experience, wisdom, and insight that merit respect and consideration. The role reversal doesn’t erase their parental identity or invalidate their perspective on their own care and life circumstances.

We can actively solicit our parent’s advice on matters unrelated to their care, creating opportunities for them to occupy their traditional parental role. This might involve asking for guidance on life decisions, seeking their perspective on family matters, or simply engaging them in conversations where they can share their knowledge and experience. These interactions remind both parties that while circumstances have changed, the fundamental relationship endures.

Managing the Psychological Weight of Caregiving

Addressing Caregiver Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

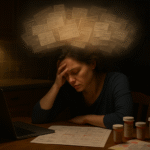

The phenomenon of caregiver burnout represents a serious threat to both caregiver and care recipient wellbeing. We experience physical exhaustion, emotional depletion, and a sense of being overwhelmed by relentless demands. Recognizing the early signs of burnout—irritability, withdrawal, decreased empathy, sleep disturbances, and physical illness—allows us to intervene before reaching crisis point.

We must prioritize self-care not as an indulgence but as an essential component of sustainable caregiving. This includes maintaining our physical health through adequate sleep, nutrition, and exercise; preserving our social connections and support networks; engaging in activities that replenish our emotional reserves; and seeking professional support through therapy, support groups, or counseling when needed.

Cultivating Self-Compassion in the Caregiving Journey

We often hold ourselves to impossible standards as caregivers, believing we should feel endlessly patient, perpetually grateful for time with our parent, and constantly joyful about the opportunity to give back. This unrealistic expectation creates guilt and shame when we inevitably experience frustration, resentment, or the desire for freedom from caregiving responsibilities.

Practicing self-compassion means acknowledging that all emotions are valid within the caregiving context. We can simultaneously love our parent deeply and feel exhausted by their care. We can value the time we have together while also longing for the independence we’ve sacrificed. These contradictions don’t make us bad children or inadequate caregivers—they make us human.

Building a Sustainable Support System

Mobilizing Family and Community Resources

Effective caregiving rarely occurs in isolation. We benefit enormously from mobilizing family members, friends, and community resources to share the caregiving burden. This might involve delegating specific tasks to siblings, coordinating with neighbors for social visits, or connecting with faith communities for emotional and practical support.

Creating a caregiving team requires clear communication about needs, expectations, and boundaries. We might develop a shared calendar for caregiving tasks, establish a communication system for updates on our parent’s condition, or organize regular meetings to assess care strategies and make collaborative decisions. This distributed approach prevents burnout while ensuring comprehensive, consistent care.

Leveraging Professional Services and Resources

Professional caregiving services provide essential support that extends our capacity and expertise. We should explore options including home health aides, adult day programs, respite care services, medical equipment providers, and case managers who can coordinate complex care needs. Financial counseling helps us navigate the economic aspects of care, while geriatric care managers offer specialized knowledge about aging-related challenges.

We must overcome any reluctance to seek professional help, recognizing that utilizing these services doesn’t represent failure or abandonment. Rather, it demonstrates wisdom and commitment to providing the highest quality care possible while maintaining our own health and wellbeing.

Finding Meaning and Growth Within the Experience

Transforming Challenge Into Opportunity for Deepened Connection

Despite its difficulties, caregiving offers unique opportunities for meaningful connection and relational deepening. We have the privilege of being present during a significant chapter of our parent’s life story. We witness their courage, resilience, and grace in facing challenges. We create new memories and discover aspects of our parent we may never have encountered otherwise.

This period allows for conversations that might never occur under different circumstances—discussions about life lessons, family history, values, and legacy. We have the opportunity to express gratitude, seek or offer forgiveness, and create closure around old wounds. These interactions, while emotionally complex, can heal longstanding relational fractures and strengthen bonds.

Personal Growth Through the Caregiving Journey

The role reversal inherent in parental caregiving catalyzes profound personal development. We discover reserves of strength, patience, and compassion we didn’t know we possessed. We develop new skills—medical knowledge, financial management, crisis navigation, and complex decision-making under pressure. We gain perspective on what truly matters in life, often experiencing a shift in priorities and values.

This growth doesn’t minimize the difficulty of caregiving or romanticize a genuinely challenging experience. Rather, it acknowledges that hardship often produces transformation, that we can suffer and grow simultaneously, and that meaning can emerge from even the most difficult circumstances.

Conclusion: Embracing the Journey With Grace and Resilience

The role reversal we experience when caring for an aging parent represents one of life’s most significant transitions. We navigate complex emotional terrain, reconstruct our identity, establish new relational patterns, and confront our own mortality—all while providing practical care and emotional support to someone we love deeply.

Success in this endeavor doesn’t mean eliminating difficulty or achieving perfect equilibrium. It means approaching the journey with intentionality, self-compassion, and realistic expectations. It means building sustainable systems of support, honoring both our parent’s dignity and our own limitations, and finding opportunities for connection and meaning within the challenge.

We must remember that the relationship between parent and child, however transformed by circumstance, endures. Our fundamental bond persists through role changes, health decline, and shifting dynamics. By navigating this transition with awareness, compassion, and courage, we honor both our parent and ourselves, creating a caregiving experience that, while difficult, embodies love, respect, and profound human connection.