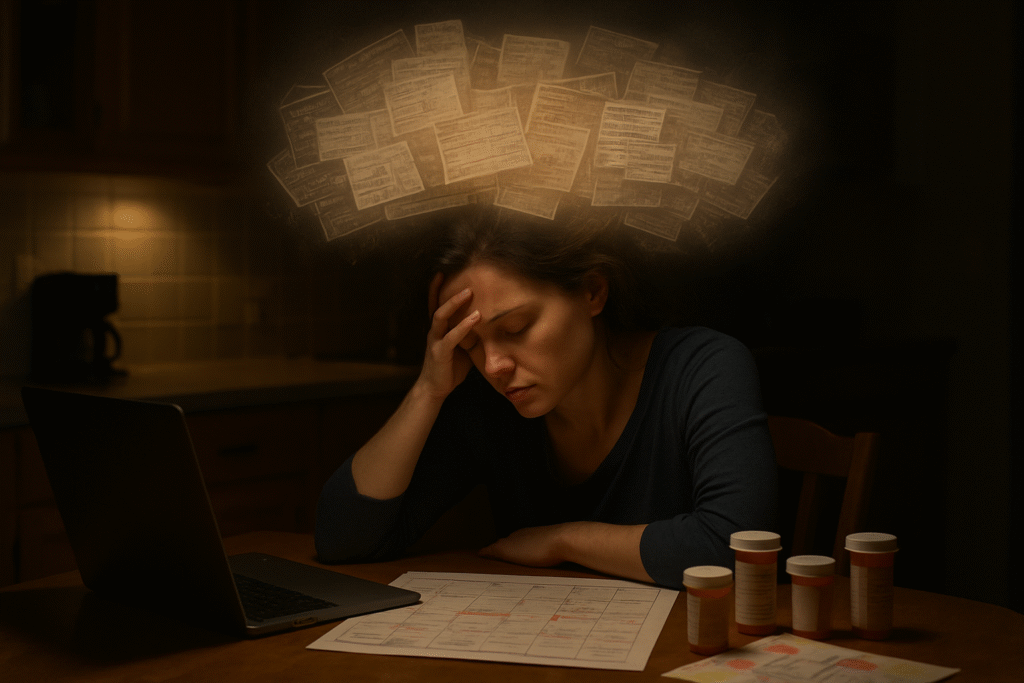

Caregiving extends far beyond the physical tasks we perform for our loved ones. While bathing, feeding, medication management, and transportation are visible and measurable, there exists a parallel universe of responsibility that often goes unacknowledged—the mental load of caregiving. This cognitive burden encompasses the planning, organizing, anticipating, and remembering that happens behind every caregiving action, creating an exhausting layer of work that never truly ends.

Understanding the Mental Load: More Than Just Stress

The mental load represents the invisible work of managing a household and caring for dependents. In the caregiving context, this load multiplies exponentially. We find ourselves constantly tracking medical appointments, remembering prescription refill dates, monitoring dietary restrictions, anticipating potential problems, and maintaining awareness of our care recipient’s emotional state—all while managing our own lives and responsibilities.

This cognitive labor operates continuously in the background of our consciousness. We wake up mentally reviewing the day’s care schedule. We lie awake at night worrying about symptoms we noticed or decisions we need to make. The mental load never clocks out, creating a state of perpetual mental engagement that leads to profound exhaustion even when we’re physically resting.

Research demonstrates that this invisible burden significantly impacts caregiver wellbeing. The constant cognitive demand depletes our mental resources, affecting decision-making capacity, emotional regulation, and overall life satisfaction. Unlike physical fatigue, which rest can alleviate, mental load fatigue requires strategic intervention and systemic change.

Recognizing the Signs of Mental Load Overload

Before we can address the mental load, we must recognize when it has become unsustainable. Many caregivers normalize their exhaustion, dismissing warning signs as simply part of the caregiving experience. However, acknowledging these indicators is essential for protecting our wellbeing and maintaining quality care.

Common manifestations include difficulty concentrating on tasks unrelated to caregiving, persistent feelings of being overwhelmed even during quiet moments, forgetting important personal commitments while remembering every detail of the care recipient’s schedule, experiencing irritability or emotional outbursts over minor issues, and feeling unable to be fully present in conversations or activities because caregiving concerns dominate our thoughts.

Physical symptoms often accompany mental load overload. We may experience tension headaches, disrupted sleep patterns, changes in appetite, or unexplained fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest. These bodily responses signal that our cognitive systems are operating beyond sustainable capacity.

The Planning Paradox: Why Good Caregivers Feel the Burden Most

Paradoxically, the most conscientious and capable caregivers often carry the heaviest mental load. Our competence becomes our burden. When we demonstrate reliability in managing complex care situations, others—including healthcare providers, family members, and even the care recipients themselves—naturally delegate more responsibility to us.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where expertise breeds responsibility, which generates more mental load, which requires us to develop even more sophisticated systems, which demonstrates greater capability, which attracts additional responsibilities. Breaking this cycle requires intentional boundary-setting and load-sharing strategies.

Creating External Systems to Reduce Internal Burden

The foundation of managing mental load lies in externalizing what we currently hold internally. Our brains are powerful but finite resources. By transferring information from our minds to reliable external systems, we free cognitive capacity for present-moment awareness and better decision-making.

Digital tools offer powerful solutions for this externalization. Shared calendar applications allow us to distribute awareness of appointments and commitments across family members or care teams. Medication management apps send automatic reminders, eliminating the need to constantly track dosing schedules mentally. Task management systems enable us to capture responsibilities as they arise rather than maintaining mental lists.

However, technology isn’t the only solution. Physical systems work equally well and sometimes better, depending on individual preferences and circumstances. A centralized care binder containing medical information, contact lists, medication schedules, and care instructions provides a single reference point that reduces the need to remember details. Visual aids like wall calendars, labeled medication organizers, and posted routines create shared awareness that distributes the mental load across everyone involved in care.

The key principle underlying effective external systems is reducing decision-making frequency. Every decision, no matter how small, consumes cognitive resources. By creating routines, templates, and standardized approaches, we eliminate countless micro-decisions that accumulate into significant mental burden.

The Power of Delegation: Sharing the Invisible Work

One of the most challenging aspects of mental load is that others often don’t see it and therefore don’t think to share it. Physical tasks are visible and easily divided, but the cognitive labor of coordination, anticipation, and planning remains hidden. Effective delegation requires making the invisible visible.

We must explicitly communicate the mental work we’re doing. Rather than simply asking someone to pick up a prescription, we might explain the entire process: noticing when supplies run low, checking which medications need refills, calling the doctor’s office if authorization is required, confirming the pharmacy has received the prescription, determining the best time for pickup based on the care recipient’s schedule, and ensuring the medication is properly stored and logged upon arrival.

When others understand the full scope of what’s involved in seemingly simple tasks, they can take on complete responsibilities rather than just executing isolated steps. This transition from task-doer to responsibility-owner represents genuine sharing of mental load.

Creating decision-making protocols also facilitates delegation. By establishing clear guidelines for common situations—when to call the doctor, how to handle medication side effects, what constitutes an emergency—we enable others to act independently without requiring our constant input and oversight.

Building Margin: The Essential Buffer Against Mental Overload

Modern caregiving culture often celebrates operating at capacity, treating efficiency as the ultimate virtue. However, systems without margin are fragile systems. When we schedule ourselves to the absolute limit, any unexpected development creates crisis conditions that dramatically amplify mental load.

Building margin means intentionally creating space in schedules, maintaining backup plans, and accepting that operating at 80% capacity is healthier and more sustainable than perpetually functioning at 100%. This might look like scheduling only two major appointments per week instead of three, maintaining a small emergency fund for unexpected care expenses, or blocking out regular unscheduled time that provides flexibility when situations change.

This approach contradicts our cultural conditioning to maximize productivity and efficiency. However, margin isn’t laziness or inefficiency—it’s strategic capacity preservation that enables us to maintain sustainable caregiving over the long term rather than burning out in months or years.

Protecting Mental Space: Boundaries as Self-Preservation

The mental load of caregiving has a tendency to expand to fill all available cognitive space if we don’t actively protect boundaries. We must create both temporal and psychological limits that preserve our mental resources and maintain our sense of self beyond the caregiver role.

Temporal boundaries involve designating specific times when we disconnect from caregiving responsibilities. This might mean establishing that after 9 PM, non-emergency caregiving concerns wait until morning, or that certain days each month are dedicated to personal priorities. These boundaries require support systems that enable us to genuinely disengage, whether through respite care, backup caregivers, or clear protocols that allow others to handle situations in our absence.

Psychological boundaries are equally important but often more challenging to maintain. They involve limiting our sense of responsibility to what we can reasonably control and accepting that we cannot prevent every possible problem or optimize every aspect of care. This requires releasing perfectionism and embracing “good enough” as a sustainable standard.

The Role of Self-Compassion in Managing Mental Load

We often treat ourselves with a harshness we would never direct toward others. When feeling overwhelmed by mental load, our internal dialogue frequently becomes self-critical: “I should be able to handle this,” “Other caregivers manage more than I do,” “I’m being weak or incompetent.” This self-criticism adds an additional cognitive burden on top of the already substantial mental load we carry.

Self-compassion represents a powerful intervention for managing mental load. This involves treating ourselves with the same kindness and understanding we would offer a friend in similar circumstances. When we notice feelings of overwhelm, rather than criticizing ourselves, we can acknowledge that we’re experiencing difficulty with a genuinely difficult situation.

Research demonstrates that self-compassion doesn’t lead to complacency or decreased performance. Instead, it enhances resilience, improves emotional regulation, and supports sustained effort over time. By reducing the secondary burden of self-criticism, we actually free cognitive resources for more effective problem-solving and caregiving.

Redefining Success: Beyond the Myth of the Perfect Caregiver

Cultural narratives around caregiving often promote an impossible standard: the selfless, endlessly patient, always-capable caregiver who meets every need while maintaining grace under pressure. This mythology not only creates unrealistic expectations but also amplifies mental load by adding the burden of measuring ourselves against an unattainable ideal.

We must actively redefine success in caregiving terms that acknowledge reality. Success might mean maintaining our care recipient’s dignity and comfort while also preserving our own wellbeing. It might mean providing good enough care rather than perfect care. It might mean asking for help before we reach crisis point rather than handling everything independently.

This redefinition isn’t about lowering standards or providing inadequate care. Rather, it’s about recognizing that sustainable, long-term caregiving requires operating within human limitations. The caregiver who maintains balance and seeks support will ultimately provide better care over time than the caregiver who burns out from attempting to do everything alone.

Creating Community: The Antidote to Isolation

The mental load of caregiving intensifies in isolation. When we’re the sole holder of knowledge, the only decision-maker, and the primary problem-solver, the cognitive burden becomes crushing. Building community represents one of the most powerful strategies for managing mental load.

This community might include other caregivers who understand the unique challenges we face, family members who share responsibility, healthcare providers who serve as partners rather than simply service providers, and friends who offer both practical support and emotional connection.

Online caregiver communities provide valuable spaces for sharing experiences, obtaining advice, and feeling less alone in our struggles. However, digital connection should supplement rather than replace in-person relationships that offer tangible support and the opportunity to genuinely disconnect from caregiving responsibilities.

The Long View: Sustainability Over Intensity

Caregiving often represents a marathon rather than a sprint, extending over months, years, or even decades. Yet we frequently approach it with sprint intensity, operating at unsustainable levels that lead to inevitable burnout. Managing mental load effectively requires adopting a long-term perspective that prioritizes sustainability over short-term heroics.

This means making choices that preserve our capacity over time, even when more intensive options seem possible in the moment. It means investing in systems and support structures that reduce long-term burden, even when they require upfront effort or expense. It means protecting our physical health, emotional wellbeing, and key relationships as essential infrastructure for sustained caregiving rather than luxuries we’ll attend to later.

The long view also includes planning for our own future. Caregivers who deplete their resources—financial, emotional, physical, and cognitive—during active caregiving years often face significant difficulties afterward. Maintaining some attention to our own needs isn’t selfishness; it’s essential foresight that enables us to sustain both caregiving and our own lives.